“We believe the leadership and workforce must work together to minimize the risks in the workplace. Our programs prepare and protect the workforce by focusing on what is needed to behave safely. Knowing and doing are very different – and the greatest risk is not the risk itself – it is how the workforce interacts with the risk on a day-to-day basis.”

—Sean G. Kaufman, CEO, Safer Behaviours

The statement by Mr. Sean Kaufman became the focal point of the BRAP Credentialing and Competency Program (BCCP) in creating a 3-session module which will give participants an in-depth awareness of the risks of working with the SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19 and it’s lab environment.

The statement by Mr. Sean Kaufman became the focal point of the BRAP Credentialing and Competency Program (BCCP) in creating a 3-session module which will give participants an in-depth awareness of the risks of working with the SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19 and it’s lab environment.

We developed this module so that he participants leave each session day with a clear understanding of the topic and not just memorizing it. Our modules are based on updated (2020) international references and the latest issuances from the Philippine Department of Health. These modules are guided by the Global Biorisk Management Curriculum (GBRMC) of Sandia National Laboratories, NM, USA. We present the 3-day module in detail here as follows.

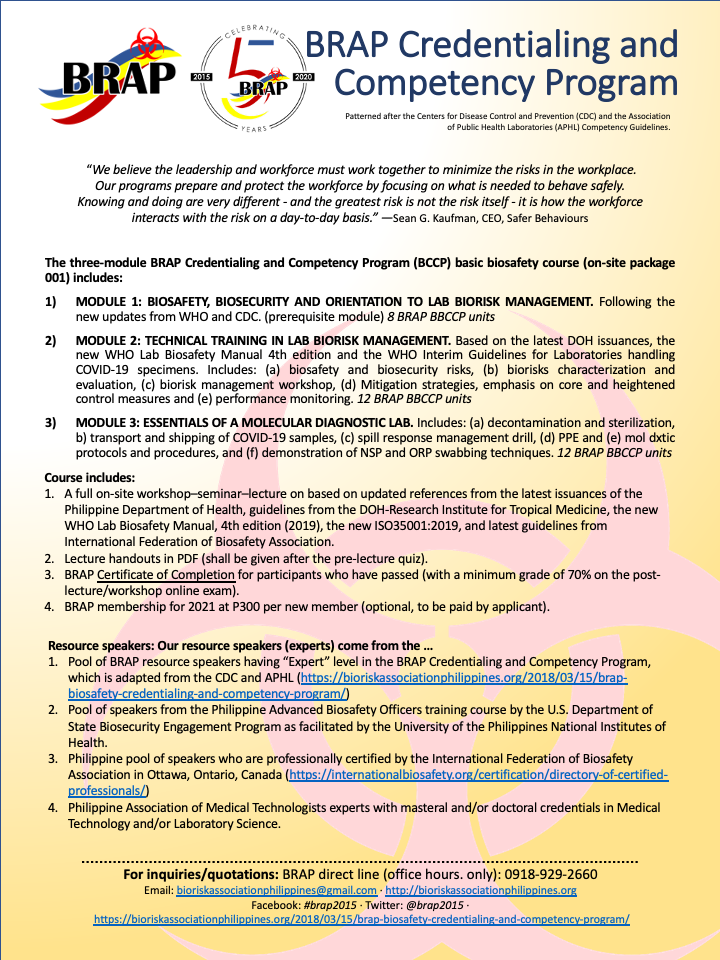

The three-module BRAP Credentialing and Competency Program (BCCP) basic biosafety course (on-site package 001) includes:

The three-module BRAP Credentialing and Competency Program (BCCP) basic biosafety course (on-site package 001) includes:

- MODULE 1: BIOSAFETY, BIOSECURITY AND ORIENTATION TO LAB BIORISK MANAGEMENT. The basic lectures for biosafety, biosecurity and a short orientation to biorisk management. Following the new updates from WHO Biosafety Manual 4th edition and the ISO35001:2019. (prerequisite module)

8 BRAP BBCCP units

- MODULE 2: TECHNICAL TRAINING IN LAB BIORISK MANAGEMENT. Based on the latest DOH issuances, the new WHO Lab Biosafety Manual 4th edition and the WHO Interim Guidelines for Laboratories handling COVID-19 specimens. Includes: (a) biosafety and biosecurity risks, (b) biorisks characterization and evaluation, (c) biorisk management workshop, (d) Mitigation strategies, emphasis on core and heightened control measures and (e) performance monitoring.

12 BRAP BBCCP units

- MODULE 3: ESSENTIALS OF A MOLECULAR DIAGNOSTIC LAB. Includes: (a) decontamination and sterilization, b) transport and shipping of COVID-19 samples, (c) spill response management drill, (d) PPE and (e) molecular diagnostic protocols and procedures, and (f) demonstration of nasopharyngeal and oro-pharyngeal swabbing techniques.

12 BRAP BBCCP units

Course includes:

- A full on-site workshop–seminar–lecture on based on updated references from the latest issuances of the Philippine Department of Health, guidelines from the DOH-Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, the new WHO Lab Biosafety Manual, 4th edition (2019), the new ISO35001:2019, and latest guidelines from International Federation of Biosafety Association.

- Lecture handouts in PDF (shall be given after the pre-lecture quiz).

- BRAP Certificate of Completion for participants who have passed (with a minimum grade of 70% on the post-lecture/workshop online exam).

- BRAP membership for 2021 at P300 per new member (optional, to be paid by applicant).

Resource speakers: Our resource speakers (experts) come from the …

- Pool of BRAP resource speakers having “Expert” level in the BRAP Credentialing and Competency Program, which is adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Association of Public Health Laboratories.(https://bioriskassociationphilippines.org/2018/03/15/brap-biosafety-credentialing-and-competency-program/)

- Pool of speakers from the Philippine Advanced Biosafety Officers training course by the U.S. Department of State Biosecurity Engagement Program as facilitated by the University of the Philippines National Institutes of Health.

- Philippine pool of speakers who are professionally certified by the International Federation of Biosafety Association in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (https://internationalbiosafety.org/certification/directory-of-certified-professionals/)

- Philippine Association of Medical Technologists experts with masteral and/or doctoral degrees/credentials in Medical Technology and/or Laboratory Science.

Package 001 course design description

MODULE 1: BIOSAFETY, BIOSECURITY AND ORIENTATION TO LAB BIORISK MANAGEMENT. This module is intended as the first module encountered by a participant in the BCCP. It is designed to offer a common understanding of the foundation and terminology of laboratory biosafety, biosecurity, biorisk management and good laboratory work practices (GLWPs) to lead the participant to better comprehension of the subject matter regardless of the role they hold. A short introductory lecture on laboratory-acquired infections is at the beginning of the course. This module is a pre-requisite course for all other courses in the BCCP.

MODULE 1: BIOSAFETY, BIOSECURITY AND ORIENTATION TO LAB BIORISK MANAGEMENT. This module is intended as the first module encountered by a participant in the BCCP. It is designed to offer a common understanding of the foundation and terminology of laboratory biosafety, biosecurity, biorisk management and good laboratory work practices (GLWPs) to lead the participant to better comprehension of the subject matter regardless of the role they hold. A short introductory lecture on laboratory-acquired infections is at the beginning of the course. This module is a pre-requisite course for all other courses in the BCCP.

Scope: this course will provide awareness of the basics of biosafety and biosecurity and an orientation to biorisk management and systems and resources to begin implementation of a biorisk management system based on the new WHO Lab Biosafety Manual 4th ed. It will also introduce students some of the practices and procedures that have been shown to mitigate, reduce, or eliminate biorisks.

Learning objectives – (based on Bloom’s taxonomy)

- knowledge, comprehension, application synthesis evaluation.

Organizational objectives

- Be able to identify GLWPs and explain why they are “good”.

- Be able to explain the importance of following proper procedure and how to get people to follow them.

Instructional objectives

- Demonstrate proper work practices, per lab-specific SOPs.

- Recognize potential unsafe work practices and conditions.

- Describe safe work practices and conditions.

- Recognize potential tasks within the laboratory’s biosafety level that have exposure hazards.

- List some general safety rules.

- Be able to explain the importance of following proper procedures.

Limitations: this module will NOT provide details on the specific components of biorisk assessment, that is, gathering information, evaluating the risks, developing a risk strategy, selecting and implementing control measures, and reviewing risks and control measures, which is found on Module 2.

Biorisk management role

- Policy makers.

- Top management.

- Biorisk management advisors/advocates.

- Scientific/lab management.

- Workforce.

MODULE 2: BIORISK MANAGEMENT. This module is intended to offer a more complete understanding of the biorisk management process from both the biosafety and biosecurity point of understanding. It includes the risk characterization and evaluation processes within biological risk assessment context that is based on the new WHO Lab Biosafety Manual 4th edition. Through guided discussion and interactive exercises, participants will be offered an introduction of risk and risk assessment in a bioscience context, followed by a discussion of the process of risk characterization, risk evaluation and its importance within risk assessment and the acceptance of risk. The participant will be made to understand and differentiate between the core requirements, heightened core measures and maximum containment measures. Final topic will be reviewing and auditing of strategies used in performance evaluation of mitigation strategies used. The participant must complete Module 1 in order to begin on this module.

MODULE 2: BIORISK MANAGEMENT. This module is intended to offer a more complete understanding of the biorisk management process from both the biosafety and biosecurity point of understanding. It includes the risk characterization and evaluation processes within biological risk assessment context that is based on the new WHO Lab Biosafety Manual 4th edition. Through guided discussion and interactive exercises, participants will be offered an introduction of risk and risk assessment in a bioscience context, followed by a discussion of the process of risk characterization, risk evaluation and its importance within risk assessment and the acceptance of risk. The participant will be made to understand and differentiate between the core requirements, heightened core measures and maximum containment measures. Final topic will be reviewing and auditing of strategies used in performance evaluation of mitigation strategies used. The participant must complete Module 1 in order to begin on this module.

Scope – While the concepts and principles are introduced in Module 1, this module further defines assessment and mitigation focusing on the new strategic framework of risk assessment (from the WHO Lab Biosafety Manual 4th ed.) by understanding by the hierarchy of controls and the advantages and disadvantages of each. Mitigation measures will also be discussed emphasizing of the Core Requirements, the Heightened Control Measures and Maximum Containment Measures. A discussion of the ISO35001:2019, the standard for Biorisk Management for the Laboratory will be given emphasis during the mitigation process. This module is a pre-requisite to any module that discusses specific mitigation control measures such as PPE, and Waste Disposal and Decontamination.

Learning objectives – (based on Bloom’s taxonomy)

- knowledge, comprehension, application synthesis evaluation

Organizational objectives

- Understand the basic concepts of risk management using the new strategic risk framework

- Know the value and use of the ISO35001:2019 standard in laboratory risk management

Instructional objectives

- Conduct a simple risk assessment by defining the work activities, hazards and being able to determine the risks

- Determine whether risk is acceptable

- List the five categories of control measures

- Understand the advantages and limitations of each

- Learn how to do a robust biorisk management and how to apply mitigation after

- Learn how to categorize various mitigation efforts into the hierarchy of controls

Biorisk Management Role

- Policy Makers

- Top Management

- Biorisk Management Advisors/Advocates

- Scientific/Lab Management

- Workforce

MODULE 3: ESSENTIAL BIOSAFETY IN A MOLECULAR DIAGNOSTIC LAB. This module is intended to provide the laboratorian with the essential biosafety and biosecurity standards, guidelines and guidance’s for one intending to work in a molecular diagnostic laboratory (MDL). The participant should have successfully completed Module 2 in order to enroll in Module 3.

Scope – Module 3 reviews the concepts of biosafety, biosecurity and biorisk management while focusing on the molecular diagnostic laboratory requiremnts. Biorisk management shall identify the biosafety level of this laboratory based on a robust risk assessment and the mitigation strategies that will be applied. Good Laboratory Work Practices, procedures and appropriate equipment shall be classified as to usage in this lab. An additional risk management lecture on engineering and administrative control measures for this laboratory. Personal protective equipment (PPE) shall be discussed with special emphasis (demo and return-demo) on proper donning ang doffing of PPE. Decontamination, Sterilization will be discussed in the Waste management part of this module. A discussion of Incident management will be included with a special lecture-demo of biological spill response drill and finally a lecture-demo & return-demo of the proper techniques of obtaining COVID samples from patients, i.e., Nasal and Oro-pharyngeal swabs.

Learning objectives – (based on Bloom’s taxonomy)

- knowledge, comprehension, application synthesis evaluation

Organizational and Instructional objectives

- Understand the role of mitigation in the new biorisk strategic framework and identify mitigation control measures based on a risk assessment of the Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory (MDL).

- Implement the basic features of an incident response system, including planning and preparation, drills & incidents, alert, assessment, mobilization, and feedback and outside coordination.

- Determine the benefits and limitations to chemical and physical methods of decontamination and sterilization.

- Describe disinfection, decontamination, and sterilization methods and explain how validation of the decontamination procedure is conducted and be able to interpret the results

- Classify and segregate different types of biological waste, and select appropriate collection and storage methods.

- Learn the proper biological or chemical spill response procedure and be able to do a good return-demo of the clean-up.

- Learn how to perform the proper technique in doing Nasal or Oro-pharyngeal swab.

Instructional objectives

- Define mitigation

- Mitigation must be based on a thorough risk assessment

- List the five categories of control measures

- Understand the advantages and limitations of each

- Know the importance of doing a thorough risk assessment prior to implementing/evaluating mitigation control measures.

Biorisk Management Role

- Policy Makers

- Top Management

- Biorisk Management Advisors/Advocates

- Scientific/Lab Management

- Workforce

For inquiries/quotations:

BRAP direct line (office hours. only): 0918-929-2660

Email: bioriskassociationphilippines@gmail.com ∙ http://bioriskassociationphilippines.org

Facebook: #brap2015 ∙ Twitter: @brap2015 ∙

https://bioriskassociationphilippines.org/2018/03/15/brap-biosafety-credentialing-and-competency-program/

To download 3-page flyer click this.

The three-module BRAP Credentialing and Competency Program (BCCP) basic biosafety course (on-site

The three-module BRAP Credentialing and Competency Program (BCCP) basic biosafety course (on-site  MODULE 1: BIOSAFETY, BIOSECURITY AND ORIENTATION TO LAB BIORISK MANAGEMENT. This module is intended as the first module encountered by a participant in the BCCP. It is designed to offer a common understanding of the foundation and terminology of laboratory biosafety, biosecurity, biorisk management and good laboratory work practices (GLWPs) to lead the participant to better comprehension of the subject matter regardless of the role they hold. A short introductory lecture on laboratory-acquired infections is at the beginning of the course. This module is a pre-requisite course for all other courses in the BCCP.

MODULE 1: BIOSAFETY, BIOSECURITY AND ORIENTATION TO LAB BIORISK MANAGEMENT. This module is intended as the first module encountered by a participant in the BCCP. It is designed to offer a common understanding of the foundation and terminology of laboratory biosafety, biosecurity, biorisk management and good laboratory work practices (GLWPs) to lead the participant to better comprehension of the subject matter regardless of the role they hold. A short introductory lecture on laboratory-acquired infections is at the beginning of the course. This module is a pre-requisite course for all other courses in the BCCP. MODULE 2: BIORISK MANAGEMENT. This module is intended to offer a more complete understanding of the biorisk management process from both the biosafety and biosecurity point of understanding. It includes the risk characterization and evaluation processes within biological risk assessment context that is based on the new WHO Lab Biosafety Manual 4th edition. Through guided discussion and interactive exercises, participants will be offered an introduction of risk and risk assessment in a bioscience context, followed by a discussion of the process of risk characterization, risk evaluation and its importance within risk assessment and the acceptance of risk. The participant will be made to understand and differentiate between the core requirements, heightened core measures and maximum containment measures. Final topic will be reviewing and auditing of strategies used in performance evaluation of mitigation strategies used. The participant must complete Module 1 in order to begin on this module.

MODULE 2: BIORISK MANAGEMENT. This module is intended to offer a more complete understanding of the biorisk management process from both the biosafety and biosecurity point of understanding. It includes the risk characterization and evaluation processes within biological risk assessment context that is based on the new WHO Lab Biosafety Manual 4th edition. Through guided discussion and interactive exercises, participants will be offered an introduction of risk and risk assessment in a bioscience context, followed by a discussion of the process of risk characterization, risk evaluation and its importance within risk assessment and the acceptance of risk. The participant will be made to understand and differentiate between the core requirements, heightened core measures and maximum containment measures. Final topic will be reviewing and auditing of strategies used in performance evaluation of mitigation strategies used. The participant must complete Module 1 in order to begin on this module.